Getting Morton Feldman’s and Samuel Beckett’s 1977 opera NEITHER from a Workshop Performance in NYC to the Konzerthaus in Vienna and the Obstacles Concerned.

Roman Maria Mueller in NEITHER

N.B. The bulk of this post comes from the Morton Feldman/Vertical Thoughts discussion list. I had written it as a response to numerous postings by a fellow composer regarding the NYC production in which I was accused of “dumbing down” the score and we were all accused of “selling out Feldman for the money.” She has never heard nor seen this production and to this day she snubs my requests for friendship on Facebook (if that’s a 21st century indicator of where things are at!). 😉

Spring 2009 – NYC

Wow. To say that reaction to this particular production have been at extremes is an understatement.

I get an email in mid-April from Eric Salzman, artistic director of the Center for Contemporary Opera. I had been recommended by long time friend and collaborator Kathleen Supove. Well, they’ve got a problem. They are presenting a Morton Feldman‘s and Samuel Beckett‘s opera NEITHER in a co-production with Vienna’s ZOON Theater directed by Thomas Desi. They’ve rented the performance materials from Universal Edition but they’re unplayable. I’ve had a copy of the full score for a number of years so I looked it over and wondered what in the hell could be done in distilling this work down to a P/V score.

So, I get it in the mail. What it is was this: somebody imploded the full score as engraved in Finale to reduce the number of systems. Some pages it’s two pianos and 1 percussion, the next page could be 7 systems and 2 percussion, c. etc. etc. In other words, it is really a study score for the soprano and not one bit of care was made to make it playable by two pianists and a percussionist. Literally, some pages had 13 note chords in each hand spread over octaves.

Salzman said that they got permission from Universal to use electronic keyboards (somehow) and that there was a very fine point in that this would not be an “arrangement.” Naturally, I thought, that¹s not how I do things and wanted whatever I came up with to be as authentic as possible within the given parameters. The CCO already had a couple of performers bail on this project so I was in a tight spot but up to the work.

Soprano soloist Kiera Duffy behind the scrim.

THIS IS HOW I DID IT: First of all, I never even looked at the P/V score since that was not a Feldman creation. I asked Universal for the Finale files of the FS but was declined. They did, but they didn’t want to get behind it. OK. Fine. Find another solution.

Percussion parts, click track, and vocal cues in Ableton

1. I recorded the 4 percussion parts by myself, multitracked, using acoustic and sampled instruments where available and how I could get it to sound best. This I did to a click that I created measure by measure as per the full score. The CCO’s budget did not allow for the hiring of one, let alone four, percussionists so this became a necessity. Also, the lack of a conductor necessitated the use of a click. Now, I’ve used a click many time before and, when one has the skill, one know how to play ahead of and behind of the click so that it can “breathe” metrically. This was the intention. Feldman’s score never deviates (as written) in tempo, his almost grid-like scaffolding was a perfect fit for this technique. When and where he wants to speed up, he uses tuplets against the grid. The trickier parts had the click adapt to these i.e. changing from and eight note click to that of quadruplets and quintuplets as the score dictated.

Michael Pilafian’s Piano Preparation

2. The acoustic piano part was easy to figure out. Michael Pilafian played the written piano, glock, and harp parts off of the full score. I had him add some voices hear and there. Harp parts (all low notes) were played on the baby grand by plucking the strings, each labeled with a piece of tape its note name. There were three sections in the piece, strategically placed, where I had Michael cover for me by playing full chords (written for 5 violas and solo cello) where I had to change program banks on my instrument. That’s what he did.

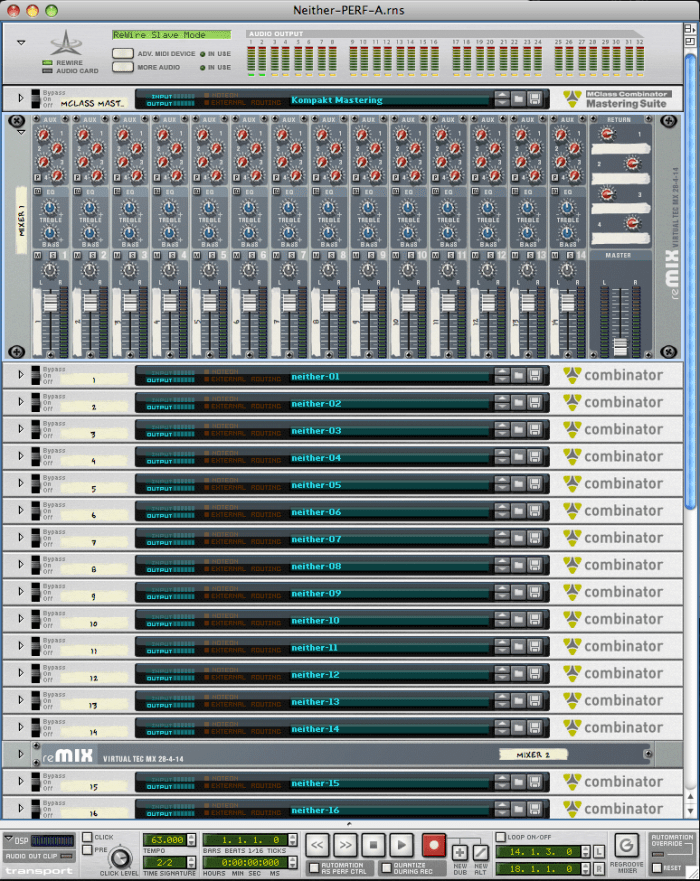

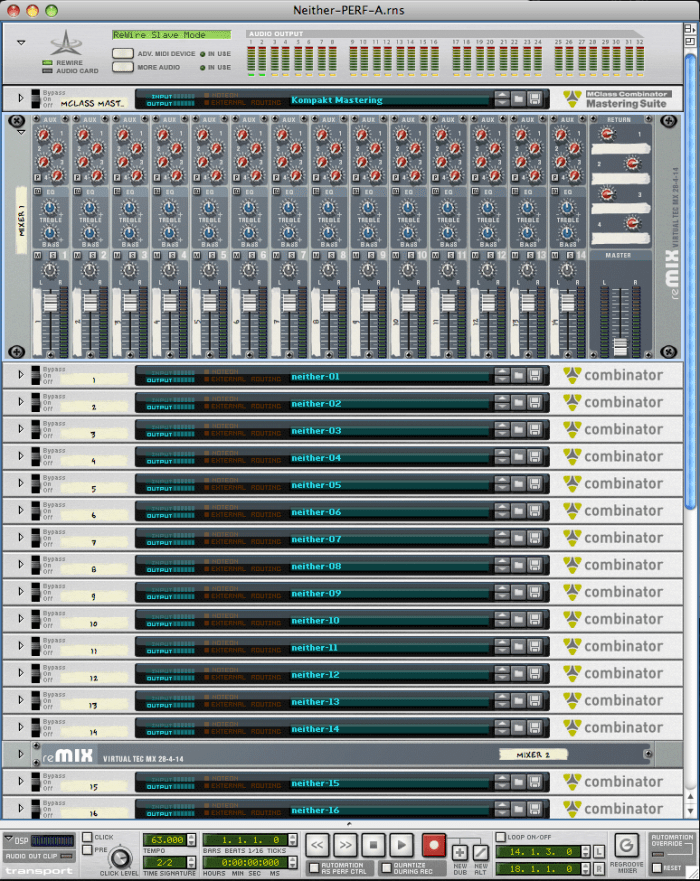

Some of the 73 Combinator patches created to perform NEITHER live in Reason 4.0

3. The Sampled Keyboard Part: This was trickiest of all. I will say, and I emphasize, not one note of the Feldman is missing, nothing had been “dumbed down,” it’s all there and I have the work to show to prove it. This was one huge puzzle for me to solve that culminated in the creation of over 70 unique programs for this piece and in my creation of what is best called a keyboard tablature score.

The keyboard tablature at rehearsal nos. 127-128

As an example: In the opening of the piece, I play the D and A above middle C but what one hears are 14 instruments, woodwinds & brass, spread across the sonic spectrum, as written by Feldman. At rehearsal number 1 I let go of the A so that only the D remains. This is where the trumpet and horn clusters were assigned. This leaves my left hand free to manually turn the know that controls the size of the filters resulting in the pulsing dynamics that are written as much as possible. And so on, and so on, until the end of the piece. Some of the keyboard tableture looks funny to read because maybe I wrote it out as a major triad, albeit with polyphonic voicing, but what one hears are orchestral samples playing the Feldman pieces, all notes and rhythms as he wrote them, as best as the … sound system at The Cell Theater would allow.

Electronic set-up for performing NEITHER live.

Above all, I did my best to keep it musical and authentic as possible. At a certain point, it is what it is, and to that I stand behind it. It is a transcription, nothing more, nothing less. Does “Wachet Auf” sound better with baroque orchestra and singers as originally written than as played on acoustic guitar? Should piano variations from a song from the White Album incite Beatlemaniacs to go and boo at a performance before even hearing it? And if any of you were at the performance, why didn’t you come up and say hello? (This last paragraph refers to Bunita Marcus’ solo piano piece Julia, a great piece, and to her various “spies” who came to the NYC performance who did not have the intestinal fortitude to introduce themselves though had plenty to say in the discussion group).

Text by Samuel Beckett

Aftermath: I was pretty nervous the second night because the people from Universal were at the performance. This nervousness was unfounded. They liked it! They want to propose it to festivals. They heard how hard I worked on it (only 2.5 weeks) and how much care and respect was given to it. Sure, who wouldn¹t want to hear a full orchestra? But in lieu of that, it’s better than gathering dust on the shelves and, if anything, may even encourage presenters to go the “full monty” and do a full production.

Also, a number of Feldman-o-philes and former students showed up and liked it too. Of course, those who thought it sucked didn’t say a word so that’s not a fair representation. Even at it¹s premiere the audience was incredibly divided. Composer Alvin Curran writes:

“dear patrick

I wish I could be there… I love this piece, and was fortunate to be at the world-premier at the Rome Opera in ???? the late 70’s — there was such a ruckus in the house that it seemed that Marcello Panni might have to stop the , then , quite awful orchestra, but in the true italian tradition they battled to the very end through a thicket of cat calls, insults…and foot-stomping. Morty was delighted to the point that he blurted to us (me and Teitelbaum) “… it’s another ‘Le Sacre’…..” Surely nothing like this will happen in nyc… but that version, staged quite appropriately by Michelangelo Pistoletto, remains a highlight of my earlier days in Rome..all best, alvin c”

Music Director/Performer Patrick Grant, Stage Director Thomas Desi and soprano Kiera Duffy.

Even Frank Oteri from the American Music Center attended. As he wrote on NewMusicBox (or as many musicians call it, NewMusicFOX, you know, “fair and balanced” and all that):

“I attended the Center for Contemporary Opera’s production of Neither. It was hard to believe that this hour-long 1977 opera with music by Morton Feldman and libretto by Samuel Beckett had never previously been presented staged in the United States. I’ve had the Wergo CD for years, and I’ve always loved the music, though I never quite “got it” as an opera. There’s admittedly little that can be got. It’s vintage Feldman, consisting of quiet repetitions of directionless angular melodies accompanied by atonal harmonies that are equally in a sonic limbo. And Beckett’s text consists of only a handful of characteristically erudite phrases.

But even though the staging compounds Neither’s elusiveness, it actually completes it. From behind a screen, Kiera Duffy sang Feldman’s unforgiving melody‹an almost impossible undertaking that she proved was possible‹while words flashed across a screen and a silent actor, Roman Maria Mueller, appeared poised to move in a variety of directions but mostly never did. It turned out to be an extremely compelling theatrical experience, believe it or not. (And more often than not I wasn’t even bothered by the piano plus sampled keyboard realization of the score.)

However, others might question whether such a piece actually communicates anything‹I was mesmerized by it although I don’t think I understood it. Therefore a piece that combines music and language in such a way ultimately contradicts the definition I just set up a few paragraphs earlier for language as distinct from music and noise. But few would probably think that Neither is noise, although surprisingly someone walked out about two-thirds of the way through, which seemed a particularly odd point to decide to spend one’s time differently; human behavior is often inexplicable. Perhaps the most rewarding aspect about any innovative work of art‹whether it is music, theatre, dance, or something in the visual arts‹is that it will ultimately tear down any definition you try to set up.”

To which he added in an email to me:

“…I thought it would seem like bad reportage if I didn’t acknowledge the fact that there was no orchestra there; sorry I couldn’t find a way to squeeze your name in there. The way that sentence was constructed, it might have seemed like I was criticizing the reduction and having your name in there might have sounded like I was criticizing you, so I didn’t add it in. But I laud you for what you did with the score; it was a Herculean effort to say the least. You might consider posting what you process was…”

I wonder if the fact that Universal Edition is a major sponsor of NewMusicBox that it had anything to do with my name being left out of the review? That’s not exactly intrepid music journalism but definitely “fair and balanced.” It’s a shame really since, not for myself so much, but that doing the piece this way was actually one of the most newsworthy facets of the production.

In building and maintaining audiences, it shouldn’t just be the concept of “new music” alone, it’s also “music that’s actually news” that will keep things fresh. I guess that’s what they mean by “thinking outside of the ‘Box.”

So there you have it. Nobody here has to like it. It’s a piece that’s known to split audiences long before I came along. Since this email list has my name popping up on Google, I just thought it best that you all know that I wasn’t “doing the Feldman for the money,” (that one’s funny), or that I chose to do this piece for “career advancement,” (???) and all the other assumptives.

Video excerpts from the May 2009 performance shot & edited by Jocelyn Gonzales.

December 2009 – Vienna

Jump cut to half a year later. Much of the hubbub has died down. Even so, my name was left off of CCO’s press releases and off of their web site regarding the Viennese production. When I brought it to their attention, I was met with a deafening silence. So, now it’s time to return the favor inherent in the co-production. We all go to Vienna to perform NEITHER in the Brut Theater within the Wiener Konzerthaus at ZOON’s invitation.

Universal Edition in Vienna’s Musikverein

The music district also contains NEITHER’s publisher Universal Edition. If anybody from there came to our sold-out performances, they never let us know.

The Brut Theater entrance of the Konzerthaus

The humble entrance to the building which saw the world premiere of the works of Beethoven, Schoenberg, and all the composers from both Viennese Schools.

Music director Patrick Grant, pianist Michael Pilafian, and ZOON Theater director Thomas Desi

It was a success and I was very happy to have done so well for Thomas Desi and the ZOON Theater. They treated us very well and showed us so much of the Viennese culture in such a short time, so warmly.

Video projections by David Haneke.

More photos from the Vienna production of NEITHER here:

http://www.zoon.at/NEITHER/index.html

Now here’s the punchline: CCO’s general manager, the great Jim Schaeffer, came to Vienna for these performances. CCO’s and ZOON’s plans (as of this writing) are to do this production with full orchestra, as Morty wrote it, on both continents again, in 2010. To get this far would not have been possible without showcasing this production the way that we did. In other words: I did such a good job that I put myself out of work. But that’s great news, really. I’m happy that this production has made it this far as a result of our original way of getting it off the ground. I hope that there’s something to be learned there for all those other “impossible to perform” pieces sitting on the dusty shelves of our 20th century classical music publishers.

I mean, does anybody think that I prefer orchestral samples to the real thing? Of course not! Am I happy that this production was helpful in exposing the music of Feldman to people who had never heard of him before, that will be drawn to the real thing, and that will garner performances done the way that Feldman had intended? Absolutely. I just did not appreciate being the whipping boy for other peoples’ projects. I just did the best that I could to be faithful to the score and, in the words of composer/performer and former Feldman student Elliott Sharp who saw the NYC production, “You did a great job. Morty would have loved it and the controversy surrounding it.” In fact, he thought that Feldman done electronically sounded a lot like The Residents (!).

So, I’m really glad to be to my music again. The work has been piling up. And when NEITHER is performed next time, I’m looking forward to my aisle seat near the back.

–Patrick Grant

UPDATE MARCH 2011: As many readers know, no further performances of the above production were permitted by the publisher. Alas! However, the New York City Opera did a great production this month in their Monodramas series. Considering that folks from the NYCO visited our production two years earlier, I wonder if theirs would have even happened had we not brought the work to their attention. I wonder. Read all about their production on their blog HERE.